Pulp's "This Is Hardcore" at 20

Three unrelated episodes:

1971: Sly & the Family Stone release their fifth album, There’s a Riot Goin’ On. It’s a commercial hit containing the no. 1 single “Family Affair,” but is in no way a buoyant work. Their previous albums reflected the nubile bliss and liberty of the hippie generation. But There’s a Riot Goin’ On is a dark, muddled, confused comedown. Disappointment and exhaustion run through the grooves. Whatever hope Sly Stone had channeled through his first four albums via cross-pollination and well-chosen substances is muted with mumbles, murkiness and shadows. It can’t help but be perceived as a hungover comment on the revolution that sputtered. Critic Greil Marcus famously says the album was “no fun.”

1985: Simon & Schuster publishes a book, Less Than Zero, by 21-year-old college student Bret Easton Ellis. It’s the story of Clay, a well-off Los Angeles college kid returning home over winter break to reconnect with old friends. Most of them have succumbed to a lifestyle of drug use, prostitution, statutory rape and faceless sex. Clay becomes both participant and passive watcher of the hedonism around him. There are no “teachable moments” in the book. Its avoidance of moral centrism is so bleak that the 1987 movie version reinvents Clay as an upright do-gooder, and to maintain a virtuous balance kills off a major character who actually survived in the original novel. (Though Ellis helpfully kills him in the sequel.)

2017: A sideshow emcee with fly-away hairpieces and property holdings ascends to the presidency of a global superpower. His oft-disputed reputation as a consummate deal-maker has given way to an obsession with media, especially television shows about sharks. This emptiest of vessels is almost universally declaimed as unfit for office, save for a battalion of red-hatted supporters with contempt for basic research and a group of would-be political profiteers looking for an inside track to ride. Aware of his own inexperience but unwilling to admit it, the president searches for motivation for incoming employees. It’s reported that in his first meeting with his staff, he advises them to, in effect, “pretend you’re on a TV series where every episode ends with you beating the bad guys.”

If these three events happened in consecutive order instead of decades apart, you’d have a fairly concise, if terribly ineffective, model of a coping mechanism: grieving, debauchery and commoditization. But what if Morpheus from The Matrix told you, “What if I told you they were all on the same album that some believe killed Britpop?”

The album was This Is Hardcore from Sheffield band Pulp, fronted by one of Britain’s best lyric-writers of the ‘90s, Jarvis Cocker. That “killed Britpop” part comes courtesy of Matthew Horton of NME, who ran the theory up the flagpole in 2013: “Jarvis Cocker had achieved everything he wanted. The spokesman for a generation tag was on his lapel and huge fame was his, but it encircled him like a cloying trenchcoat, every fibre wanting a piece of him. This Is Hardcore… is a sloughing-off of fame’s skin, a rejection of the Britpop monster. That monster could have been him, could have been the moribund wasteland around him.”

It’s not a bad theory. But it’s not enough. It doesn’t explain how shattering This Is Hardcore remains 20 years hence.

Still, let’s run with Horton’s theory for the moment: Britpop, which produced a handful of golden moments, was suffocated by its own grandiloquence, helped along by a British tabloid culture not especially known for being the model of temperance in a frenzy. While Oasis unveiled unifying anthems a la Beatles and Blur pecked out more locally-based portraits a la Kinks, Cocker and Pulp worked the inside game and questioned everybody’s motives.

Although they never implicated any of the bands they were told to be rivals of, Pulp’s albums served as reality checks for the sovereign hysteria of Britpop. What interested Cocker were the sexual and class politics of the people who bought the records.

Pulp earned their conjectures the hard way. Breaking out after a decade of recording with 1994’s surprise hit His ’n’ Hers, Pulp made their biggest and maybe best album, Different Class, in 1996. Songs like “Common People” and “Disco 2000” were more concerned with interactions that spoke to caste-definted roles in society—accounts that recast the Swinging London stories of Colin MacInnes in the last days before the Internet.

Examined strictly in context of its time, This Is Hardcore isn’t just Cocker taking the piss out of Britpop: It’s a full-on urological drain with spillage and bits of liver. NME would have you believe Cocker was shedding his status as the form’s most trenchant figurehead. He does so by ego-reduction in “Dishes” (“I am not Jesus, though I have the same initials”), or by becoming a con man (“Help the Aged,” “Seductive Barry”) or a monster (half the fucking album). Then he declares the whole thing dead (“The Day After the Revolution”). Regimes are supposed to fall when this much demystification’s at play.

Since it came after Britpop’s peak, it’s reasonable to suggest the style was in Pulp’s crosshairs on This Is Hardcore. But if that’s all it was, the album wouldn’t hold up as well as it does now. Cocker had more than champagne supernovas, whatever the hell they are, in his sights. The demise he sensed was an entire conception, a global shift out of a program that looked nice on paper but couldn’t sustain itself, like on There’s a Riot Goin’ On (“You can’t leave cause your heart is there/But, sure, you can’t stay cause you been somewhere else”). Managing one’s distress with such failure could require absolution through mechanistic, outwardly sensuous activities with no guilt, like in Less Than Zero (“There are some guys sitting at tables who all look at this one gorgeous girl, longingly, hoping for at least one dance or a blow job in Daddy’s car and there are all these girls, looking indifferent or bored, smoking clove cigarettes…”). As for the dopey president, sit tight, we’ll get to him.

Pulp lays out the premise right up front as Cocker introduces the newest dance craze, “The Fear.” After a prolonged adolescence full of youthful sexual and social dramas, the terrible angst of middle age sets in—and that terror is just as seductive as powdered smart drinks and having back-seat sex with “Parklife” on the stereo: “A monkey’s built a house on your back/You can’t get anyone to come in the sack/And here comes another panic attack.” Forget fishnets, stiletto heels or buckle restraints: Fear is the new fetish in town. The gothic-lite chorus is a parody of the catchall singalongs that unified warring factions in the ‘80s; it’s like “We Are the World” with all the singers’ joined hands fastened together with thumbscrews.

At first Cocker tries to bargain with humility in “Dishes.” He’s just the help, really. He’s not the Britpop hero he’s made out to be, nor Jesus, not Willem Dafoe as Jesus, nor Liam Gallagher on one of his rare lucid days. “I’d like to make this water wine, but it’s impossible/I’ve got these dishes to dry.” It’s both touching and absolutely insincere. Of course he’s no miracle worker, but why did he even consider that was a possibility?

Cocker starts recusing himself on “Party Hard,” with the hysterically funny one-liner “Entertainment can sometimes be hard.” These are the last vestiges of meaningful inquiry we get for a few songs, as he’s about to abandon all hope that his date’s going to be as inquisitive as he is: “Before you enter the palace of wisdom/You have to decide: Are you ready to rock?” The wonderfully pathetic “Help the Aged”—Cocker was a ripe old 33, remember—reframes May-December lust as a charitable contribution, or a smashingly awful pickup strategy. “When did you first realize/It’s time you took an older lover, baby?/Teach you stuff, although he’s looking rough.” It’s a more sinister version of “When I’m Sixty-Four,” minus grandkids, plus unsolicited groping.

The title track, among so many other things, marks the first of a few repeated mentions of mass media on the album. “This Is Hardcore” kickstarts the album’s moral and empathetic decline with undulating brass. Cocker’s character is working off the simulated ecstasy that he’s seen in porn, having taken notes on the lighting and blocking, imagining that this sporting round of fornication is going to be fucking amazing. But by the end, for some reason, he reverses track and disparages the act: “That goes in there/Then That goes in there/And that goes in there/And that goes in there/And then it’s over.” It’s not satisfying in the least. But it’s hardcore. It’s a process. It’s escalation, not satisfaction. Now even sexual congress with a willing partner is only masturbation.

“TV Movie” references a time when made-for-television movies or regular series weren’t nearly as critically accepted as they are now; they were seen as flimsier cinema substitutes for people who didn’t get out much. (Think today’s Hallmark Network.) Without his partner in attendance, it’s just 90 minutes of wasted frames. Immediately after that comes Pulp’s most heartbreaking song, “A Little Soul” (the music video of which is equally sad). Cocker’s character realizes his neglected child has picked up on his dismissive treatment of women, and is likely to repeat the same offenses that caused the singer’s wife to go away: “You look like me, but please don’t turn out like me… I look like a big man, but I’ve only got a little soul.”

“I’m a Man” continues exploring Cocker’s by-now ruptured scrutiny of masculinity which has been running for five straight songs at this point. He’s absorbing the media again, finding that the images of manhood they used to promote are losing their cachet. It all leads to a circuitous life with constant exertion and no payoff. Then comes “Seductive Barry,” an 8-minute deconstruction and overhaul of the creamy spoken-word disco of Barry White. It’s at least a bit more sympathetic and genuinely sexy than the title track, but Cocker still forces the sounds of machinery in there and hasn’t quite got the empathy down yet: “I don’t expect you to answer straight away, maybe you’re just having an off day.” Jeez, do you speak at funerals with that mouth?

“Sylvia” and “Glory Days” both reset the singer to When Times Were Better. Sylvia’s a mysterious woman who still haunts him, even though he never did quite enough to form a real connection with her. He’s paid for it, and apparently so has Sylvia. “Glory Days” lionizes a time of social unity and good feelings, even though nobody seems to remember exactly what the specific accomplishments were: “I did experiments with substances/But all it did was make me ill/And I used to do the I Ching/But then I had to feed the meter.” As Jack Nicholson’s most stereotypical character said, “What if this is as good as it gets?”

To wrap up, Cocker does the dramatically prudent thing and declares everything dead. “The Day After the Revolution” taunts the platitudes and grand statements that usually come associated with sweeping pop music, treating the rebellion with all the importance of what he had for breakfast: “Oh, sorry, you haven’t heard? We are the children of the new world.”

The album’s final breakthrough comes when Cocker declares “the meek shall inherit absolutely nothing at all.” Every act he’s committed on This Is Hardcore—every self-consuming activity or deflating self-assessment—is rendered clean by the realization that a little ego trumps a little soul (compare with Michael Tolkin’s 1994 yuppies-in-crisis satire The New Age). And just to remind you what forces drove this sudden awakening, he openly disagrees with Gil Scott-Heron: “The revolution WAS televised.” The album ends with an invocation of everything an aging gallant no longer has to bother with: “Perfection is over/The rave is over/Sheffield is over/The Fear is over/Guilt is over/Soul is over/Bergerac is over/The hangover is over/Men are over/Women are over/Cholesterol is over/Tapers are over/The breakdown is over/Irony is over/Bye bye.”

Depressing? Sure it is!

But also significant, and portentous for all the most uncomfortable reasons. Popular culture is envisioned as a series of touchstones and mascots that unify mass groups of people—whether through acceptance or revulsion, it supposedly brings people together. Jarvis Cocker, though, presents it as a dissociative force. Its ideas are undeveloped. Its critical mass is oppressive. And for every kumbaya circle it inspires, it estranges individuals who aren’t helping to move the meters or make the tastes.

Cocker’s narrative moves through “The Fear” of losing one’s youth to a sad place of helplessness, where even if one’s as classically jaded as Cocker they’re still vulnerable to suggestion. Which is where the media comes in. All of the narrator’s ideals and comparisons come from visual representation: the porn movies of the title track, the “bad dialogue, bad acting” of “TV Movie,” the “advertising sliding past my eyes” of “I’m a Man.” He’d rather be a grudging recipient of those screens’ information than an active thinker. And, as we in the colonies have observed recently, that’s all a spray-tanned dolt with an asshole-shaped pout really needs to form a presidential working strategy: Just do it like they do on TV (except The West Wing—that Sorkin guy uses too many big words, it’s just talk-talk-talk all the time, bing bang bing bang bong).

This Is Hardcore can’t just be about the limits of Britpop. It’s about every popular rage that ever happened, and it’s about any 33-year-old person dealing with emotional displacement (except for that other J.C.). The “hardcore” isn’t just the circus sexual acts or the self-serve nose candy (which Cocker reportedly used while making this album). It’s also the emotional comeuppance that takes place, whether its feelers know what it is or not.

Or, if you prefer, “hardcore” is the unattainable. When Cocker’s done with the action phase in the title track, he asks “What exactly do you do for an encore? ‘Cause This Is Hardcore.” There’s supposed to be a cumulative ending, a super-orgasm, or at least a fatal train wreck. Something to punctuate the hardcore: the hardest core imaginable. Instead there’s just a flickering screen with a test pattern and underwear you’ll have to wash at some point.

Twenty years later, that’s still pretty much all there is. And then it’s over.

Song by Song

“The Fear” - “This is our ‘Music from a Bachelor’s Den’,” Cocker opens the album, referring to a series of lounge-music reissues that were popular at the time (think Capitol’s Ultra Lounge project). With a chorus that simulates the themes from Italian horror movies and spaghetti westerns, paranoia is the new hip thing no bachelor can be without. The song references its own existence: “The chorus goes like this… pretty soon you’ll all be singing along.” When that happens in an album’s first song, you can usually assume it’s a disclaimer for the rest of what you’re about to hear. The album’s best one-liner might be in the first verse: “A horror soundtrack from a stagnant waterbed.” Ask your “free-thinking” aunt if you have questions about waterbeds in the ‘70s.

“Dishes” - Cocker envisions himself as a stay-at-home dad, performing modest tasks for the usual low level of thanks or outward appreciation. It’s a sad fanfare for the common man, or would be if one could possibly envision Cocker in this role, which one could not in 1998. But for you and me, it probably works just fine: “I’m not worried that I will never touch the stars/‘Cause stars belong up in heaven and the earth is where we are.” Still, when Cocker sings “Aren’t you happy just to be alive?”, it’s impossible not to hear the gentle sarcasm.

“Party Hard” - Musically it apes David Bowie’s “Look Back in Anger” from Lodger. But instead of getting a visit from an angel with crumpled wings, Cocker’s date encounters a man who dumps his spooge on her “best party frock.” First of all, who wears a frock to a party? (Well… older people, I suppose.) And the man’s misguided missile seems a more committed expression than the pantomime of a good time everyone thinks they’re having. When your date sings “Baby, you’re driving me crazy” through a Vocoder, your night’s almost guaranteed to be a disappointment, unless you’re seeing a guy from Kraftwerk.

“Help the Aged” - The album’s first single is its best joke, an absurd pickup scenario that almost makes sense. No gap is as difficult to bridge as those between generations, but bless this fossil for trying: “Help the aged/One time they were just like you/Drinking, smoking cigs and sniffing glue.” Kind of puts a damper on all those sunny youths singing “Live Forever” at the back of Wembley Arena, but technically he’s not lying. Musically the song moves like Radiohead’s “Creep,” except this singer seems to believe that he was so fucking special when he was young and didn’t have to comb shit over.

“This Is Hardcore” - There’s not much I can add about this song that isn’t covered in the main article. It’s ugly and unfulfilling, and that is not a complaint. The eerie horn arrangements came via a sample of German composer Peter Thomas, who scored a lot of movies in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The highly-regarded music video for “This Is Hardcore” does exactly what you don’t expect: Rather than simulate hardcore pornography, director Doug Nichol restaged Hollywood movies (especially film noir) from the ‘40s through the ‘60s, ending with a sprawling Busby Berkeley dance sequence with Jarvis Cocker sullenly traipsing through a minefield of frozen-smiled dancers and way too many feathers.

“TV Movie” - Probably the most unremarkable track on This Is Hardcore, but it’s about someone who is dealing with his lack of remarkability. Cocker’s vulnerability is plainspoken and mundane: “Is it a kind of weakness to miss someone so much? To wish the day would go away…like you did yesterday?” But that may be the point: The singer’s aware that his dull expressions mimic the prepackaged sentiment from cheap TV movies. Like “The Fear” and “This Is Hardcore,” this song’s lyricism might be its own meta-joke.

“A Little Soul” - Cocker’s most disconsolately beautiful song draws from the musical blueprint of Smokey Robinson’s “Tracks of My Tears.” “A Little Soul” shows the unforeseen casualty of a life spent chasing hipster ideals and studied coolness: the chance that same indifference gets passed down to one’s offspring by proxy. The accompanying video is even sadder, as directors Hammer & Tongs show Pulp’s adult band members in half-awake states, with lookalike children morosely trying to move them toward some kind of action or reaction. The burdens parents pass on to their children has never been more poignantly shown.

“I’m a Man” - By this point the whole of masculinity has been compromised, so what better time to uncork the album’s most typically Britpop moment? Cocker rifles through the images of manhood as proffered by media: the distant schmoozer of Mad Men nine years before the series debuted, and the lizard feeling the ill effects of self-satisfaction (“So you stumble into town and hold your stomach in”). It’s all a “waste of time,” Cocker sings in one of the album’s few moments where you’re sure he’s not joking.

“Seductive Barry” - An opus that simulates both the pace and length of erotic soul genius Barry White—only without the climaxing string sections and quite so much grunting. But Cocker’s proposition is far less confident than White’s, revealing perhaps a little more than a loverman should in the coital environment: “When I close my eyes I can see you lowering yourself to my level… How many others have touched themselves whilst looking at pictures of you?” Guest vocalist Neneh Cherry is de-emphasized almost to the point of muteness—which, again, may be the narrative point.

“Sylvia” - Like Deborah from “Disco 2000,” Sylvia’s a part of Cocker’s distant memory, but with a more complicated record. Some of it isn’t fully explained (“Her beauty was her only crime”), some of it’s believable without needing too much detail (“He don’t care about your problems/He just wants to show his friends”). There may be something in how Cocker shifts from talking to a person who reminds him of Sylvia to addressing Sylvia herself, without acknowledging the transfer. But why does Cocker advise—whoever it is he’s advising, Sylvia or alt-Sylvia—to “please stop asking what it’s got to do with you”? Is it so much out of her control?

“Glory Days” - The most rousing song on This Is Hardcore pulls from the assumed (often misheard) message of sunny Britpop: “Raise your voice in celebration of the days that we have wasted.” The difference is that Cocker’s “celebrating” cerebral accomplishments: “Learn the meaning of existence/in fortnightly installments/Come share this golden age with me/In my single-room apartment.” But ambition plays no part in the glory; in fact the committed refusal of others’ idea of advancement is partly why it’s so glorious. This might be what Cocker would have said to the girl in “Common People” if she didn’t really want to sleep with common people.

“The Day After the Revolution” - This also is sufficiently explained in the main piece. The version of this song on the deluxe edition of This Is Hardcore features an extended ending which just consists of a single synthesizer chord droning on for 10 minutes. Cocker interrupts it once, at a somewhat arbitrary point, with a sudden “bye bye.”

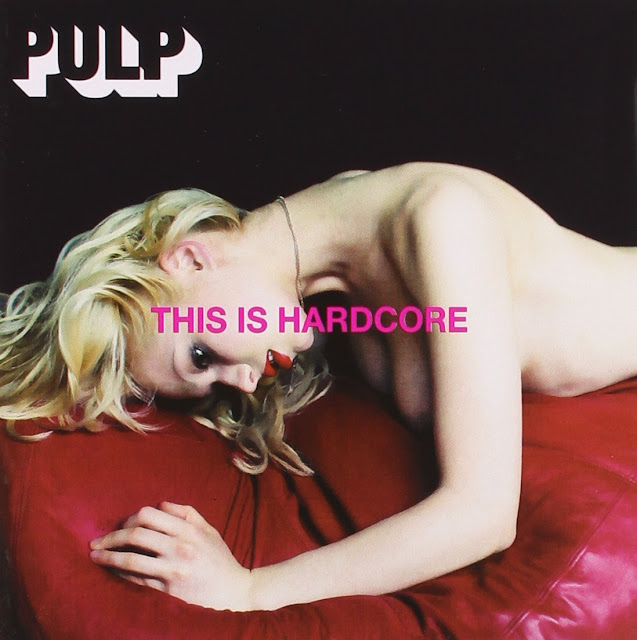

The Cover

Graphic designer Peter Saville constructed This Is Hardcore’s iconic cover art, with a naked woman (nipples obscured) flung across a red vinyl sofa cushion, the album’s title in hard pink splashed across her cheek and upper arm. Her face has a dead expression, but her positioning is alert.

At Cocker’s urging, Saville collaborated with American painter John Currin for the packaging of the album, as well as the artwork for the singles. Currin specialized in hyper-realism, in which subjects are treated as in a high-resolution photograph. This allows the artist to emphasize certain subtleties or disquieting features about the subjects they’re painting. In the case of the cover of This Is Hardcore, Currin’s input influenced photographer Horst Diekgerdes to take stark photos of human subjects which Saville then “hyper-realized” with some computer manipulation.

The image was used for posters that dotted London Underground subway tunnels. As expected, they were met with some protests. Graffiti blasted the artwork as objectification, and newspapers like The Independent declared that the “woman looks as if she had been raped.” (I do not believe that is the only acceptable interpretation of the model’s positioning at all. It’s one of several possibilities.)

Of course, objectification is a running theme of This Is Hardcore. Minimized emotions and implied violations are part of the ongoing narrative. If you look closely at the model there’s the slightest plasticine glint, an almost mannequin-esque expression across the woman’s face. Like the title song itself, the tension of the cover rests in whether what’s depicted is actually a real thing, or a projected, airbrushed fantasy.

Comments